UPDATED 22 May 09:15

The New York Federal Reserve President made some suprising comments at a talk at the Japan Society. Among other things, he revealed that the Fed balance sheet expanded as a by-product of transferring private long-term risk to the Fed. He also said that the Quantity Theory of Money that many expected would create inflation from the Fed’s loose money, was largely circumvented because money has mostly stayed with the banking system. He also thought that the “exit strategy” revealed in the Fed’s 2011 minutes had gone “stale” and needed to be refreshed.

William Dudley, President of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, made news in four respects at his talk at the Japan Society early this afternoon. Two of the news-worthy comments came during the Q&A session after Dudley had delivered his prepared remarks, “Lessons at the Zero Bound: The Japanese and U.S. Experience”.

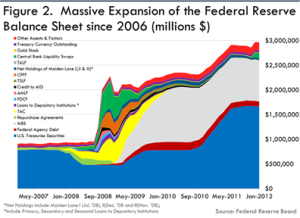

First, in his prepared remarks, President Dudley described the expansion of monetary reserves, and the size of the monetary base (and, therefore, the expansion of the Fed balance sheet) was a by-product – not the goal – of the Fed’s monetary policy. The objective was to transfer longer term risk held by the private sector – primarily Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities –to the Fed’s balance sheet. This was intended “to push down risk” premiums, and prompt “private sector investors to move into riskier assets.” “As a result, financial market conditions ease, supporting wealth and aggregate demand,” Dudley said.

First, in his prepared remarks, President Dudley described the expansion of monetary reserves, and the size of the monetary base (and, therefore, the expansion of the Fed balance sheet) was a by-product – not the goal – of the Fed’s monetary policy. The objective was to transfer longer term risk held by the private sector – primarily Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities –to the Fed’s balance sheet. This was intended “to push down risk” premiums, and prompt “private sector investors to move into riskier assets.” “As a result, financial market conditions ease, supporting wealth and aggregate demand,” Dudley said.

Second, in the Q&A session, Dudley inferred that the Quantity Theory of Money (MV=PQ), as well known to generations of Econ 101 students as “Goodnight, Moon” is to generations of children, is now mostly irrelevant or even obsolete. The Fed has had the ability to pay interest on excess reserves since October, 2008. This ability allows the Fed to keep money (“M”) in the banking system, on deposit at the Fed, so that it cannot circulate to create “V”, or velocity.

This was probably Dudley’s most important comment of the day, as it tends to explain why the inflation most had anticipated remains so low and why many small and medium sized businesses find banks tight-fisted in their lending, notwithstanding the massive expansion of the Fed balance sheet.

When the law change came into effect in early October, 2008, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke gave the impression that he was somewhat bewildered with what he was to do with the new “tool” Congress had given him. Now we know: it allows the Fed to print money without inflation, bolster banks’ reserves for stress tests, and send old theorems into the waste bin – at least for the time being.

Dudley answered a question about the distinction between Fed policy that keeps interest rates low to reach “critical mass” or “escape velocity” for a domestic economy versus one that is intended to “beggar thy neighbor” by engaging in currency manipulation. Dudley said that the Fed generally leaves that determination to the Treasury a nd that it does not consider the trade implications when setting monetary policy.

nd that it does not consider the trade implications when setting monetary policy.

Finaly, President Dudley said that it might be better to let the long-term agency and Treasury obligations it has acquired to passively “burn off” (i.e., be held to maturity) rather than be sold at a loss. This would be a revision of the exit strategy outlined in the Fed minutes for June, 2011, which Dudley called “stale”. That strategy called for long term agency securities to be sold off over three to five years. This seems to be a political – rather than an economic – judgment by Dudley. His colleague, James Bullard, of the St. Louis Fed, has expressed concern about the political risks to the Fed if it sold agency debt acquired from private holders at a loss and such losses are so deep that the Fed would be required to suspend payments to the Treasury for the first time since the 1930’s.

In other comments during his prepared remarks, President Dudley indicated that the Fed had probably not used enough stimulus at the outset of the financial crisis and that the Fed should have been better in communicating its goals, erring in communicating that the Fed liquidity would be short-term and drawn back on a particular calendar date instead of the circumstances of the economy. He also said that the Fed had persistently overestimated growth.

Overall, Dudley framed his comments in the context of six “Lessons From the Zero Bound,” the zero or near-zero rates of interest that Japan and the USA have both used to stave off deflation and a liquidity trap. At the “zero bound”, central bankers cannot reduce interest rates any further to stimulate growth in GDP; they are “bound”by the zero rate of interest. An “interest rate” below zero is deflation, where dollars with less purchasing power are used to pay nominal debt and interest. When deflation occurs, creditors lose money by lending, inventories lose their nominal value, and borrowers– whose incomes have generally shrunk—pay more in terms of real purchasing power to repay any nominal debt they incurred prior to the deflation; that is, they pay more in terms of real purchasing power than they incurred in debt.

Dudley’s lessons from Japan’s – and the US own – experience is that, at the zero bound, central bankers must 1.) manage expectations of the central bank policy; 2.)communicate with a single voice that is clear and not muddled and act according to what it communicates; 3.) asset purchases help to communicate that the Fed will “ease financial conditions to support growth and keep inflation expectations well anchored”; 4.)all of the instruments of policy – including communicating objectives – must work so that they are more effective collectively than they are separately; 5.) risk management vis. interest rates and inflation becomes critical because, once in a liquidity trap, its extremely difficult to emerge; and, 6.) monetary policy has limits, particularly at the zero bound. Fiscal policy must play a role in moving the economy from recession.

The text of President Dudley’s speech is available at the NY Fed Website.

Recent Comments